You can also listen to this article on YouTube at the linke above. A PDF version is on my website here. Follow me on Twitter: @xriskology, and support my work, if you’d like, here.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The main text of my new book, Human Extinction: A History of the Science and Ethics of Annihilation, is 457 pages long, or around 200,000 words. That’s a lot to read. So, I thought it might be useful to outline some of the key ideas of Part I and Part II. In brief:

Part I is an intellectual history of thinking about human extinction (mostly) within the Western tradition. When did our forebears first imagine humanity ceasing to exist? Have people always believed that human extinction is a real possibility, or were some convinced that this could never happen? How has our thinking about extinction evolved over time? Why do so many notable figures today believe that the probability of extinction this century is higher than ever before in our 300,000-year history on Earth? Exploring these questions takes us from the ancient Greeks, Persians, and Egyptians, through the 18th-century Enlightenment, past scientific breakthroughs of the 19th century like thermodynamics and evolutionary theory, up to the Atomic Age, the rise of modern environmentalism in the 1970s, and contemporary fears about climate change, global pandemics, and artificial general intelligence (AGI).

Part II is a history of Western thinking about the ethical and evaluative implications of human extinction. Would causing or allowing our extinction be morally right or wrong? Would our extinction be good or bad, better or worse compared to continuing to exist? For what reasons? Under which conditions? Do we have a moral obligation to create future people? Would past “progress” be rendered meaningless if humanity were to die out? Does the fact that we might be unique in the universe—the only “rational” and “moral” creatures—give us extra reason to ensure our survival? I place these questions under the umbrella of Existential Ethics, tracing the development of this field from the early 1700s through Mary Shelley’s 1826 novel The Last Man, the gloomy German pessimists of the latter 19th century, and post-World War II reflections on nuclear “omnicide,” up to current-day thinkers associated with “longtermism” and “antinatalism.”

In the book, I call the first history “History #1” and the second “History #2.” For the most part, History #1 shaped the trajectory of History #2, although I argue that this relationality reversed, in a momentous way, at the turn of the 21st century, when ethical considerations about the extreme “badness” of extinction influenced how a number of quite influential people came to think about our collective existential predicament in the universe.

As you can see in this Google Ngram Viewer graph, the frequency of references to “human extinction” increased after World War II, spiked in the 1980s, and since the 1990s has more or less exponentially risen. One of the central aims of the book is to explain why this is the case.

Both histories are dominated by white men. This is largely due to the fact that the overwhelming majority of people who have written about human extinction have been white men; indeed, there are perhaps only 30 or so Western philosophers—that’s it—who have offered anything close to a systematic analysis of the ethics of extinction. Why it is that privileged white men have dominated Existential Ethics is a question that I hope to address in subsequent papers. The most obvious answer is that an extinction-causing catastrophe would directly affect them, whereas non-extinction catastrophes like global poverty and localized famines, and social injustices like racism and sexism, do not. Worrying about human extinction and occupying a privileged position in society have been intimately connected.

Let’s take a closer look at History #1 and History #2. In order to make sense of History #2, though, we will need to examine a number of theoretical issues. Hence, the following document is divided into three main sections. The first summarizes History #1. The second lays the theoretical groundwork for Existential Ethics. And the third summarizes History #2. I conclude with a short summary of some key ideas. Although I will pass over quite a bit of important detail provided in the book, this will give readers a good overview of the territory that I cover.

Section 1. History #1—Existential Moods

1.1 The Five Existential Moods

Since virtually nothing has been written about the history of thinking about human extinction within the West, I had no obvious point of departure. (The image below shows an early attempt to make sense of this history, from 2019.) So, I voraciously read everything that I thought might be even slightly relevant, hoping to discover some kind of historical patterns.1 To my surprise, this is exactly what I found: four major shifts in how people within the West have understood our existential predicament in the universe. These shifts are clearly defined, and each unfolded very abruptly. They are sudden revolutions in our thinking about human extinction, each accompanied by figurative and often literal gasps.

I characterize the five periods—separated by four shifts—in terms of the prevailing “existential mood.” This is a type of “public mood,” as in the “mood of the times,” whereby large numbers of people are oriented in the same general direction, toward a particular outlook on humanity’s future—indeed, on whether we will even have a future at all. An existential mood arises from a particular set of answers to fundamental questions about our existential predicament, such as: Is our extinction even possible? One might believe that it is not, perhaps because one thinks that God would never allow it. If it is possible, though, a second question arises: could it actually happen? Perhaps we happen to live in a universe that is completely safe—not on an individual level, of course, but on the level of our species: there just aren’t any ways that humanity itself could disappear. I call a “way that humanity could disappear” a kill mechanism, examples being nuclear war and a global pandemic. Additional questions include: if there are kill mechanisms stalking humanity, how many? Are they natural or anthropogenic? How likely is it that a kill mechanism catapults us into the collective grave? Is this probability rising or falling? Could extinction happen in the near term? Is our extinction inevitable in the long run? And so on.

Hence, an existential mood is defined by how credible figures at some point in time answered these questions. As noted above, the shift from one set of answers to another has in every case been extremely rapid, while the answers given between each shift in mood have been remarkably stable, with very little change. That said, although the shifts in existential mood were abrupt, it is useful to distinguish between when a mood first emerged and when it fully solidified. The five existential moods are:

(1) The ubiquitous assumption that humanity is fundamentally indestructible. This mood dominated from ancient times until the mid-19th century. Throughout most of Western history, nearly everyone would have said that human extinction is impossible, in principle. It just isn’t something that could happen. The result was a reassuring sense of “Comfort” and “perfect security” about humanity’s future, to quote two notable figures writing toward the end of this period. Even if a global catastrophe were to befall our planet, humanity’s survival is ultimately guaranteed by the loving God who created us or the impersonal cosmic order that governs the universe.

(2) The startling realization that our extinction is not only possible in principle but inevitable in the long run—a double trauma that left many wallowing in a state of “unyielding despair,” as the philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote in 1903. The heart of this mood was a dual sense of existential vulnerability and cosmic doom: not only are we susceptible to going extinct just like every other species, but the fundamental laws of physics imply that we cannot escape this fate in the coming millions of years. This disheartening mood reverberated for roughly a century, from the 1850s up to the mid-20th century.

(3) The shocking recognition that humanity had created the means to destroy itself quite literally tomorrow. The essence of this mood, which percolated throughout Western societies in the postwar era, was a sense of impending self-annihilation. Throughout the previous mood, almost no one fretted about humanity going extinct anytime soon. Once this new mood descended, fears that we could disappear in the near future became widespread—in newspaper articles, films, scientific declarations, and bestselling books. Some people even chose not to have children because they believed that the end could be near. This mood emerged in 1945 but didn’t solidify until the mid-1950s, when one event in particular led a large number of leading intellectuals to believe that total self-annihilation had become a real possibility in the near term.

(4) The surprising realization that natural phenomena could obliterate humanity in the near term, without much or any prior warning. From at least the 1850s up to the beginning of this mood, scientists almost universally agreed that we live on a very safe planet in a very safe universe—not on an individual level, once again, but on the level of our species. Though humanity might destroy itself, the natural world poses no serious threats to our collective existence, at least not for many millions of years, due to the Second Law of thermodynamics. Nature is on our side. This belief was demolished when scientists realized that, in fact, the natural world is an obstacle course of death traps that will sooner or later try to hurtle us into the eternal grave. Hence, the essence of this mood was a disquieting sense that we are not, in fact, safe.

(5) The most recent existential mood—our current mood—is marked by a disturbing suspicion that however perilous the 20th century was, the 21st century will be even more so. Thanks to climate change, biodiversity loss, the sixth major mass extinction event, and emerging technologies, the worst is yet to come. Evidence of this mood is everywhere: in news headlines declaring that artificial general intelligence (AGI) could annihilate humanity, and the apocalyptic rhetoric of environmentalists. As we will discuss more below, surveys of the public show that a majority or near-majority of people in countries like the US believe that extinction this century is quite probable, while many leading intellectuals have expressed the same dire outlook. The threat environment is overflowing with risks, and it appears to be growing more perilous by the year. Can we survive the mess that we’ve created?

A close examination of the historical record, I argue, reveals these five existential moods. I consider this to be a discovery rather than invention: Western history really does consist of five distinct periods, each corresponding to a different set of answers about fundamental questions concerning our existential predicament. The more I looked into this, searching for disconfirming evidence, the more incontrovertible the periodization became.

I should add a nuance about the first existential mood: there were some early thinkers who envisioned humanity dying out, such as the ancient Greek philosophers Xenophanes, Empedocles, and the Stoics. All believed not just that our extinction is possible, but that it is unavoidable. However, they also believed that, after disappearing entirely, humanity would always reappear. In Xenophanes’ account, the cosmos cycles through two stages: wetness and dryness. During the stage of wetness, all life vanishes, though it returns during the stage of dryness; this happens over and over again for eternity. Using terminology that I introduce later on in the book, Xenophanes and the other ancient philosophers believed that we would undergo “demographic extinction” (we disappear entirely) but not “terminal extinction” (we disappear entirely and forever). The view that humanity is indestructible is thus compatible with belief in our extinction.2

Hence, the notion of human extinction dates back to the ancient world, even though the very same individuals who posited “demographic” extinction as a future inevitability also accepted our indestructibility in a broader cosmic sense. Yet this idea that we are fundamentally indestructible took on a much more radical form with the rise of Christianity, which saw our extinction in even the most minimal sense as impossible. Indeed, Christians would have argued that the concept of human extinction is quite literally unintelligible, incoherent, or self-contradictory, not unlike the concepts of married bachelor and circles with corners, for reasons discussed below. Historically speaking, Christianity became widespread in the Roman Empire around the 4th or 5th centuries CE, and maintained a stranglehold on the Western worldview until the 19th century, when it declined significantly among the intelligentsia. It was this century that Friedrich Nietzsche famously declared that “God is dead” and Karl Marx described religion as the “opium of the masses.” The 19th century is when atheism became popular among the educated classes, though it wasn’t until the 1960s that, to borrow a phrase from the theologian Gerhard Ebeling, the “Age of Atheism” commenced and a secular outlook spread throughout society more generally.

1.2 Enabling Conditions

The periodization above is a story of psycho-cultural trauma—of realizing that we are not a permanent feature of the universe, and in fact nature or humanity itself could nudge us over the precipice of extinction in the very near future, maybe within our own lifetimes. But what explains this periodization? Why did these shifts occur? Why did they occur when they did, rather than some other time? How did this all happen?

This is where I introduce an explanatory hypothesis, which I argue could also be used to predict how the idea of human extinction might evolve in the future. It consists of two parts: enabling conditions and triggering factors. Let’s consider these in turn:

As the term “enabling conditions” suggests, this refers to conditions that enabled the idea of human extinction to no longer be an unintelligible impossibility to many people in the West. Since Christianity is what rendered human extinction an unintelligible impossibility after its rise in the 4th or 5th centuries CE, it was the secularization of Western civilization—i.e., the decline of Christianity—that made human extinction look like a real possibility. In particular, it was the dissolution of two clusters of beliefs, both central to the Christian worldview for roughly 1,500 years, that opened up the conceptual space needed to see our extinction as something that could, at least in principle, happen.

The first cluster is the Great Chain of Being. I call this a “cluster” because it consists of three component ideas: the principle of plenitude, principle of continuity, and principle of unilinear gradation, which we needn’t go into detail about here. The Great Chain is a model of reality according to which everything that exists can be ordered into a linear hierarchy: God is at the top, followed by angelic beings, humans, animals, zoophytes (transitional species), plants, and minerals at the bottom. Crucially, the model assumed that it is impossible for any links in the chain to go missing, even temporarily. This might sound strange to contemporary ears, but the Great Chain was hugely influential for a millennium and a half. Its influence was absolutely pervasive, as Arthur Lovejoy explores in his magisterial book The Great Chain of Being (1936). Since the extinction of anything is fundamentally impossible, the Great Chain implies that our own extinction is impossible, too. Hence, this first cluster of beliefs made a general point about extinction.

The second cluster consists of what I call the ontological and eschatological theses. These make a specific point about humanity, and hence if one accepts them, one will believe that our own extinction is impossible even if one believes that the extinction of other species can happen. The ontological thesis states that humanity is immortal, because each member of humanity is immortal. We are immortal because, according to standard Christian anthropology, we consist of an immortal soul that, once created, will never cease to exist. This explains why the idea of human extinction would have seemed incoherent or self-contradictory to believers. To say that “humanity can go extinct” would be to say that “an immortal type of thing can undergo a process that only mortal kinds of things can undergo,” which is an obvious logical contradiction. As I write in a footnote, “immortal human” is a pleonasm whereas “human extinction” is a contradiction.

The eschatological thesis states that humanity cannot go extinct because our extinction, in a naturalistic sense, isn’t part of God’s grand plan for humanity and the cosmos. Eschatology is the “study of last things,” and a key aspect of Christian eschatology is balancing the scales of cosmic justice when the world ends. In our world, the wicked are often rewarded, while the righteous sometimes finish last. That is unjust. At the end of time, though, God will rectify this problem. But how can the scales of cosmic justice be balanced if humanity were to cease existing entirely? The show cannot go on without us, and since the show must go on, we cannot go extinct. Human extinction just isn’t on the cards for us; it isn’t how our story ends.

That’s not to say that Christians don’t anticipate an “end to the world.” On the Christian view, however, the world’s end coincides with the beginning of eternity, which contrasts with the idea that extinction would entail our complete and permanent non-existence. Roughly speaking, Christians anticipate a future transformation, while human extinction constitutes our termination.

It was these two clusters of beliefs that rendered human extinction an unintelligible impossibility for roughly 1,500 years. Our extinction, in other words, would have been simply unthinkable. In the very early 19th century, a brilliant French anatomist named Georges Cuvier dealt a mortal blow to the Great Chain: he proved that some species have in fact gone extinct. This was a revolutionary idea that exploded the Great Chain model of reality.3 The eschatological thesis was weakened the previous century, during the Enlightenment, because of the rise of deism. Generally speaking, deists do not accept special revelation—the “truths” supposedly delivered by supernatural deities, such as God or angels, to prophets like John of Patmos, who supposedly wrote the Book of Revelation. Consequently, many Enlightenment deists did not accept the eschatological (end-times) narrative of Christianity. Nonetheless, the influence of the eschatological thesis declined most resolutely with the general fall of Christianity throughout the 19th century, at least among the intelligentsia. This is also when the ontological thesis became untenable, due partly to the theory of evolution proposed by Charles Darwin in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. Although Darwin avoided the topic of human evolution in his book, the theory he put forward clearly implies that Homo sapiens, our species, evolved in a gradualistic manner from various “lesser” forms. It was difficult to square this with the idea that we are ontologically unique compared to all other creatures, because we have immortal souls and they don’t. If we are different from the rest of life in degree rather than kind, there is no more reason to believe that we are immortal than to believe that chimpanzees are.

Note that the eschatological thesis and, especially, the ontological thesis persisted after the Great Chain collapsed. Hence, it was still widely believed that humanity could not go extinct, even if other species can. The decline of these two theses is what finally enabled human extinction to become an intelligible possibility. This was a shocking realization.

1.3 Triggering Factors

This brings us to “triggering factors.” Consider this: have you ever worried about walking past an outlet in the wall and being shocked by a bolt of electricity leaping out from it? What about a car that’s currently on the other side of the country running you over on the sidewalk right now? We don’t worry about such things because we know they cannot happen: it just isn’t the way our world works. If there isn’t good reason to believe that something could actually happen, we probably don’t give it much thought. The same goes for extinction. Even if this is possible in principle, if there are no actual kill mechanisms—means of elimination—lurking in the shadows, there may be no particular reason to think much about human extinction. Hence, the discovery of kill mechanisms played an integral role in shaping History #1. In many cases, this is what triggered shifts to new existential moods, which is why I call them “triggering factors.”

Although Western history is full of speculations about global-scale catastrophes, dating back at least to the mid-17th century BCE with the epic poem of Atrahasis, it wasn’t until the 1850s that the first scientifically credible kill mechanism was identified. This was the Second Law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy (basically, disorder) of an isolated system will tend toward a maximum. Physicists, followed by everyone else, immediately recognized the dismal implications of this: Earth will become increasingly inhospitable to life, until no life at all is possible. Our days are numbered, even if we were to somehow escape Earth: the universe as a whole will ultimately sink into a frozen pond of eternal lifelessness—a state of thermodynamic equilibrium called the “heat death.”4 Since there is no escaping the dictatorship of entropy, many came to despair that human existence may be meaningless. What does anything matter if, in the end, all will be lost?

It is remarkable to see that, prior to the 1850s, almost no one fretted about or even considered the possibility of human extinction. After this decade, anxieties about the long-term fate of humanity in an atheistic universe governed by the Second Law were common.5 This is what catalyzed the first, abrupt, traumatic shift in existential mood. Before this shift, questions like “Is our extinction possible?,” “Could our extinction actually happen?,” and “Is our extinction inevitable” were all answered with “no.” Not long after, most educated secular people answered them in the affirmative. Hence, it was the decline of Christianity in the 19th century along with the discovery of the Second Law that, together, introduced a new existential mood, which descended on the West with a heavy, heart-wrenching thump.6

Since human extinction was no longer seen by everyone as impossible, this period also witnessed a flurry of novel speculations about how we might die out. Some suggested a planetary conflagration, sunspots that blot out the sun, cometary impacts, global pandemics, large boilers (high-tech of the day) that obliterate Earth by exploding, and even evolutionary forces causing humanity to “degenerate” into one or more lesser species, as explored by H. G. Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine. Especially after World War I, with its horrors of tanks, poison gas, and flamethrowers, many feared that technological advancements could yield terrible new weapons that kill everyone on the planet. Yet none of these proposed kill mechanisms was widely accepted at the time. The only kill mechanism that scientists agreed on was the Second Law of thermodynamics.

As alluded to above, this changed with the invention of nuclear weapons in 1945. Surprisingly, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not lead to widespread discussions of anthropogenic extinction, although many media outlets reported on these attacks using rather apocalyptic language. But virtually no one linked atomic bombs with human extinction. The focus was instead on the possibility of civilizational destruction, with atomic bombs being seen as (much) bigger hammers that states could use to smash each other to bits. This is captured by a line from a US lieutenant that, if World War III is fought using nuclear weapons, the war after that one will be fought “using spears,” which is often attributed to Einstein, who may have read the news article containing the original statement. In other words, the worry wasn’t that we will annihilate ourselves, but that atomic bombs could slingshot humanity back into the Paleolithic.

It wasn’t until 1954 that people began to explicitly worry about our extinction, and indeed the shift in language from before and after this year is astounding. What happened in 1954? This is when the US tested a thermonuclear weapon—a “hydrogen” rather than “atomic” bomb—in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific, which produced an explosive yield 2.5 times larger than expected. Thermonuclear weapons are much more powerful than atomic weapons, and this event—the Castle Bravo test—catapulted large quantities of radioactive particles into the atmosphere. The result was an international incident with Japan, as a number of Japanese fishermen came down with radiation sickness. More important for our story is that the particles from the Castle Bravo test were detected around the world. Suddenly, it became terrifyingly obvious that even a small-scale thermonuclear conflict between the US and the Soviet Union could blanket our globe with lethal amounts of radioactivity. Radio addresses listened to by millions of people warned that self-annihilation is now a real possibility, and statements signed by world-renowned physicists, including Einstein, declared that a war between the US and Soviet Union could turn Earth into a radioactive hellscape that no human could endure. This was the second credible kill mechanism—global thermonuclear fallout—and it’s what triggered the shift to a horrifying new existential mood, marked by a sense of impending self-annihilation.

Yet this was just one of several kill mechanisms proposed during the postwar era. In 1962, the marine biologist Rachel Carson argued that synthetic chemicals released into the environment could have mutagenic effects, degrading our germ plasm—the genetic material passed down to all future generations—and potentially ending humanity. Others warned about overpopulation and ozone depletion, followed by the discovery of a new type of kill mechanism associated with nuclear weapons: the nuclear winter scenario. Still others, channeling the general anxieties of the time, speculated about genetically engineered pathogens, artificial intelligence systems that self-improve until they are far “smarter” than humans, and even advanced nanotechnology that could convert the biosphere into what one theorist called “gray goo.” Over the course of just a few decades, people went from believing that the only actual kill mechanism was the Second Law to believing that we face a multiplicity of near-term threats to our collective survival. Whereas the Second Law wasn’t scheduled to end humanity for many millions of years, thermonuclear war, environmental degradation, and other such human-caused threats could bring this about on timescales relevant to contemporary people. This was a very frightening transition to a new, darker, more menacing world.

Yet for almost the entire Cold War era, virtually no scientists believed that nature itself—aside from the Second Law—poses any real threats to our existence. This was because of a paradigm in the Earth sciences called uniformitarianism, which essentially states that sudden, catastrophic events can occur on the local level (we know this, of course, because we witness volcanoes, tornadoes, floods, and the like), but never on a planetary scale. Global catastrophes just don’t happen, even if some people, in earlier times, had speculated about things like cometary impacts. This just isn’t the way our universe is. Uniformitarianism became influential in the 1830s, and by the 1850s was widely accepted. It maintained a stranglehold on the Earth sciences until the 1980s and early 1990s, when a series of revolutionary discoveries caused its spectacular implosion.

It all started in 1980, when a team of scientists proposed that the dinosaurs died out 66 million years ago because a giant asteroid struck Earth. Throughout the 1980s, this was hotly debated, with most paleontologists rejecting the idea. Of note is that the hypothesis lacked a smoking gun: if a massive impactor hit Earth, it should have left behind a huge crater. But where is this crater? No one had a clue—that is, until a graduate student discovered the Chicxulub crater buried underground, beneath the Yucatan Peninsula. This discovery was published in 1991, and over the course of just a few months, virtually the entire scientific community came to the shocking realization that uniformitarianism is wrong and global catastrophes caused by natural phenomena can happen. The ominous implications of this were immediately recognized: if global catastrophes have happened in the past, they can happen again in the future. We are not, in fact, living on a very safe planet in a very safe universe. At some point in the future, nature is going to try to commit filicide—the killing of one’s children.

This bombshell triggered yet another shift in existential mood, corresponding to a different set of answers to the questions mentioned earlier. The threat environment was getting more and more crowded, not just by anthropogenic risks but by natural dangers as well. Indeed, once Earth scientists were extricated from the uniformitarian paradigm, they began to speculate about other natural risks, such as volcanic supereruptions, which some linked to a near-extinction event for humanity some 75,000 years ago, after a supereruption in Indonesia spewed huge quantities of sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere, blocking out the sun for many years. It turns out that nature is an obstacle course of existential hazards—not just threats from above, like asteroids and comets, but risks from below, associated with geophysical phenomena on our terrestrial home.

Our most recent existential mood emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The shift to this mood was a little bit different than previous shifts, because it wasn’t triggered by the discovery of any new kill mechanisms. Rather, it resulted from two important developments that unfolded in parallel. The first is rather complicated. In the 1980s and 1990s, a number of philosophers began to think seriously about the ethical implications of our extinction. They concluded that human extinction would constitute a moral tragedy of quite literally cosmic proportions, not so much because a catastrophe that wipes out Homo sapiens tomorrow would kill billions of people on Earth, but because no longer existing would prevent humanity from realizing vast amounts of “value” in the future.7 This means that avoiding extinction is really, really important. But how can we avoid our extinction? The obvious answer is to neutralize all the known threats to our survival: nuclear war, asteroidal assassins, volcanic supereruptions, and so on. What if there are risks that we don’t yet know about? What if something leaps out from the shadows of our collective ignorance and buries us alive, before we even know what’s happened?

These questions launched a number of philosophers on a mission to catalogue every possible risk to our survival, however speculative, hypothetical, improbable, or exotic. This includes dangers that don’t currently exist but might later on this century, a shift toward thinking about potential 21st-century risks that I call the “futurological pivot.” By mapping out the entire threat environment, stretched across the diachronic dimension of time, we will optimally position ourselves to neutralize all these risks, thereby ensuring our safe passage through the obstacle course ahead.

This was the first triggering factor: ethical considerations, associated with History #2, spurred a radical remapping of the threat environment, foregrounding what the futurist Ray Kurzweil called in 1999 “clear and future dangers.” Once an exhaustive list of all the present, emerging, and anticipated future threats was compiled, it became apparent that the 21st century will be far more perilous than the 20th century, due largely to “GNR” technologies, where “GNR” stands for “genetics, nanotech, and robotics,” the last of which includes artificial intelligence. What lies ahead should make us shudder, though many of the same figures who became anxious about the future—I call them “riskologists”—also believed that if advanced technologies do not destroy us, they will usher in a techno-utopian world of endless abundance, immortality, and unfathomable pleasure.

The second triggering factor arose from new research on anthropogenic climate change, biodiversity loss, and the sixth mass extinction, which showed that these are far more catastrophic than previously understood. It might be surprising to know that it wasn’t really until the 2000s that climatologists and environmentalists saw such threats as dire. Some climate scientists had, of course, warned about carbon dioxide altering Earth’s thermostat decades earlier—and it would have been wise to listen to them. But as the historian Spencer Weart notes, the “discovery” of global warming wasn’t “complete” until the very early 2000s, at which point scientific debate about the matter effectively ceased. Since then, the overwhelming consensus has been that climate change is real and anthropogenic, and the window for meaningful action to prevent a climate catastrophe is rapidly closing. Along similar lines, it wasn’t until the year 2000 that the concept of the “Anthropocene” was added to our shared lexicon of ideas. While climate change and the Anthropocene loom large in the environmental movement today, they were largely or entirely off the radar of environmentalists throughout the 20th century.

Together, these two developments paint a dismal picture of the future. The dangers are enormous and almost certainly growing, as the climate crisis worsens and the march of scientific and technological “progress” accelerates. This is our current existential mood: the worst is yet to come. Evidence of this mood is everywhere, as noted above: one recent survey found that roughly 40% of Americans believe that climate change will cause our extinction. Another reports that 54% of people in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia rate “the risk of our way of life ending within the next 100 years at 50% or greater.” Earlier this year, a survey from Monmouth found that 55% of Americans are “very” or “somewhat worried” that advanced artificial intelligence will annihilate us.

Many prominent scholars agree with the public. Noam Chomsky declared in 2016 that the risk of human extinction is “unprecedented in the history of Homo sapiens,” while Stephen Hawking warned the same year that “we are at the most dangerous moment in the development of humanity.” Even pro-technology TESCREALists like Nick Bostrom put the probability of extinction before 2100 at 20%. The direness of our existential predicament is perhaps best encapsulated by the Doomsday Clock, which is currently set to 90 seconds before midnight, which represents doom. By comparison, the closest the Doomsday Clock came to midnight during the Cold War was in 1953, after the US detonated the first thermonuclear weapon. That year, the minute hand was placed at a “mere” 2 minutes before doom. According to the Doomsday Clock, our current situation is more perilous than anytime during the 20th century. And there is every reason to believe that the minute hand will inch forward in the years to come.

1.4 Existential Hermeneutics

The backdrop to the most recent shifts in existential mood has been, of course, the enabling condition of secularization. Without a secular worldview, few people would believe that human extinction, in a naturalistic sense, is even possible. This points to another important idea in Part I of the book, which I call an “existential hermeneutics.” By this I just mean a lens through which to interpret the dangers surrounding us. The key idea is that the threat environment isn’t a given—the world must be interpreted, and it’s this interpretation that yields the threat environment. Existential hermeneutics are lenses through which to interpret dangers, and they can be religious or secular to varying degrees. Two people with radically different hermeneutics might look at the very same dangers and come to opposite conclusions about the riskiness or significance of those dangers—about whether to be frightened or not. Put differently, how one maps the threat environment depends on two things: first, a particular model of the world, which may be more or less empirically accurate. And second, the hermeneutical lens through which this model is filtered, thus yielding the threat environment. The threat environment, as one sees it, can therefore change if either of these two variables is altered.

Consider the case of nuclear weapons. While secularization in the West accelerated greatly during the 1960s, there were still plenty of people in the latter 20th century who embraced the ontological and eschatological theses. They believed that humanity is immortal, and that we play an integral role in God’s grand plan for the cosmos. Consequently, they did not believe that thermonuclear war could cause our extinction, and hence were not worried about this outcome. Instead, they integrated the new threat of nukes into the end-times narrative of the Bible. As I write in the book, end-times prophesies are both rigid and highly elastic, often able to accommodate unforeseen developments as if the Bible predicted them all along. Ronald Reagan provides an example. In 1971, while he was governor of California, he declared that,

for the first time ever, everything is in place for the battle of Armageddon and the Second Coming of Christ. … It can’t be long now. Ezekiel [38:22] says that fire and brimstone will be rained upon the enemies of God’s people. That must mean that they’ll be destroyed by nuclear weapons. They exist now, and they never did in the past.

For Reagan and other evangelicals, the possibility of a nuclear holocaust was filtered through the lens of a religious hermeneutics. Consequently, their mapping of the threat environment was completely different than the mapping of atheists like Carl Sagan and Bertrand Russell. The latter two did not see nuclear weapons as part of God’s grand plan to defeat evil. Rather, a thermonuclear Armageddon would simply be the last, pitiful paragraph of our species’ autobiography. Whereas for Christians, the other side of the apocalypse is paradise, for atheistic individuals it is nothing but oblivion. In this way, secularization played an integral part in enabling the discovery and creation of new kill mechanisms to alter the threat environment and, with these alterations, to induce shifts from one existential mood to another.

1.5 Looking Forward to the Future

I claimed above that the combination of enabling conditions and triggering factors yields not just an explanation of the five existential moods, but could also allow us to make predictions about how our thinking about human extinction might evolve in the future. I’ll give two quick examples to illustrate the predictive component of this hypothesis.

First, is there any reason to believe that we’ve discovered or created every possible kill mechanism? Just four decades ago, nearly all scientists believed that asteroids and volcanoes cannot cause global catastrophes. What other natural phenomena, deadly dangers lurking in the cosmic shadows, might haunt us? What might we discover in the future? Alternatively, what new technologies might we create that could pose unprecedented threats to our collective survival? Just as Charles Darwin’s mind would have been boggled by the thought of nuclear weapons and genetic engineering, perhaps there are inventions that we cannot now even begin to anticipate. If there are new kill mechanisms discovered or created in the future, these could initiate yet another shift in existential mood. We should anticipate this possibility with a high degree of trepidation.

Second, is there any reason to assume that the trends of secularization will continue in the future? History is full of religious revivals. Although these trends appear robust—one study even argues that religion is racing toward “extinction” (their word) in nine Western countries—it’s not impossible that they reverse. If that were to happen, we could return to the first existential mood, with many people coming to believe that humanity is, in fact, fundamentally indestructible. For atheists, this might be quite frightening, since a world run by extinction denialists that is simultaneously full of catastrophically dangerous technologies looks like a highly combustible situation. It could even hasten a global disaster, as religious extremists take it upon themselves to use these technologies to bring about the apocalypse. During the Cold War, some evangelical Christians argued that the US shouldn’t try to make peace with the Soviet Union, since a nuclear Armageddon with the “Evil Empire” is all part of God’s plan for the world. As the televangelist Jim Robins said during the 1984 Republican National Convention: “There’ll be no peace until Jesus comes. Any preaching of peace prior to this return is heresy; it’s against the word of God.” Similarly, when Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, James Watt, was asked about “preserving natural resources for future generations,” he dismissively responded: “I do not know how many future generations we can count on before the Lord returns.”

Not all religious people hold such extreme beliefs, of course. Many religions have a very good track record with respect to, say, taking climate change seriously. And, of course, one need not believe that human extinction is possible to worry about global-scale catastrophes from climate change, pandemics, and artificial intelligence. The point is that if Christianity reemerges in the West, there will likely be some who adopt radical views. If the past is any indication, these people could rise to the highest levels of political power, which may be disconcerting.

In sum, there have been five distinct existential moods in Western history. All four shifts in mood were enabled by the decline of Christianity, which continues up to the present. The first three of these shifts were triggered by the discovery of new kill mechanisms, while the forth was triggered by a combination of ethical considerations and novel research in the environmental sciences. One can think of these existential moods as a palimpsest, with each mood layered on top of previous ones, the only exception being the first mood, which was replaced by the second. Our current existential mood is marked by a fairly pervasive sense that the worst is yet to come, due largely to the dangers associated with emerging technologies and the catastrophic failure of our political leaders to address the environmental crisis.

Section 2. Existential Ethics—The Basics

NOTE: I have updated the ideas discussed in this section. Much of what I write below is directionally correct, I would now argue, but some nuances miss the mark. (As a professor told me when I was an undergraduate, sometimes one needs to write an entire book to really understand what one is trying to say!) For my current thinking about the best way to navigate the ambiguities of “human extinction,” see this paper, forthcoming in the philosophy journal Synthese. I’d recommend reading it instead of this section, and then continuing with section 3, which I still very much stand by. Thank you!

[Content Warning: The next two sections contain a reference to suicide.]

2.1 Types of Human Extinction

Questions about whether our extinction is possible, how it could happen, what its probability is, and so on, are distinct from questions about whether it would be right or wrong to bring about (ethical questions) and whether it would be good or bad, better or worse if it were to happen (evaluative questions). I call the study of these ethical and evaluative questions “Existential Ethics.” Part II of the book traces the historical development of Existential Ethics from its birth in the 19th century up to the present.

However, to understand this history, it is necessary to disambiguate some terms and sketch the general topography of positions that one could accept within Existential Ethics. The most important term to disambiguate is “human extinction.” It may seem odd that I wait until Part II to address this issue. I do so because, first of all, understanding the different definitions of “human extinction” is rather complicated, and Part I is convoluted enough as it is. Second, the primary subject of History #1 is “human extinction” in what I call the prototypical sense, which is the most intuitive conception of extinction. This means that it wasn’t, strictly speaking, necessary to delve into such detail. I’ll say more about the prototypical conception in a moment. Third, distinguishing between different types of human extinction is a prerequisite for making sense of Existential Ethics. Many ethical theories about our extinction don’t just concern the prototypical sense, but other types of human extinction as well. This is why disambiguating the term is crucial for Part II of the book.

2.2 What Is Humanity?

The term “human extinction” is ambiguous because both “human” and “extinction” are ambiguous. The most obvious definition of “human” equates it with Homo sapiens, our species. Yet if you were to ask an anthropologist, they would say that “human” means our genus Homo, which includes a range of species from Homo habilis, the very first humans, to Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals), and Homo sapiens, the only surviving human species today.

Whereas this provides a backward-looking perspective, there are also future-looking definitions, which are especially relevant to Existential Ethics. The futurist Jason Matheny uses “‘humanity’ and ‘humans’ to mean our species and/or its descendants.” I take this to encompass all populations of future beings that are genealogically or causally related to us. Another futurist writes that “by ‘humanity’ and ‘our descendants’ I don’t just mean the species [Homo] sapiens. I mean to include any valuable successors we might have,” later describing these as “sentient beings that matter.” This adds a normative dimension to the definition: it’s not just future beings that are genealogically or causally related to us, but beings that are valuable or matter in a moral sense. If they don’t matter in this sense, they won’t count as “human.”

Along similar lines, the longtermists Hilary Greaves and William MacAskill stipulate that “human” refers “both to Homo sapiens and to whatever descendants with at least comparable moral status we may have, even if those descendants are a different species, and even if they are non-biological.” In other words, future beings that are genealogically or causally related to us—our descendants—will count as human only if they possess a certain moral status. The most capacious definition comes from the neo-eugenicist Nick Bostrom, who defines “humanity” as “Earth-originating intelligent life.” This would include “intelligent” creatures that might evolve entirely separate from us, on a completely different lineage. If Homo sapiens were to die out tomorrow but these beings were to emerge 1 million years from now, then “human extinction” wouldn’t have happened.

It is worth noting that we do not yet have good terminology for these ideas. Consider that Bostrom and others would classify radically “enhanced” future people as “posthumans.” Yet on most of the definitions given above, these posthumans could also count as “humans.” Hence, the same being could be both posthuman and human, which is obviously confusing. I explore this problem in the book, but do not propose any new terms to clarify the issue.

In what follows, I will assume as a default that “human” means Homo sapiens, deviating from this definition when necessary.

2.3 What Is Extinction?

These are a few ways that “human” or “humanity” can be defined. But what about “extinction”? If you ask an evolutionary biologist, they’ll say that there are many different kinds of extinction that species can undergo: demographic, phyletic, functional, ecological, and so on. Some of these are relevant to the case of humanity, although I believe there are other extinction types that are unique to us. In the book, I argue that there are six distinct human extinction scenarios that are ethically, evaluatively, and historically important. All of these build upon a “minimal definition” of extinction, which is pretty straightforward:

Minimal Definition: Something S has gone extinct if and only if there were instances of S at some point in time, but at some later point in time, this is no longer the case.

This is meant to be a general definition, which could apply no less to cultures and languages than to biological species. With respect to humanity, the minimal definition could be satisfied in at least the following six ways:

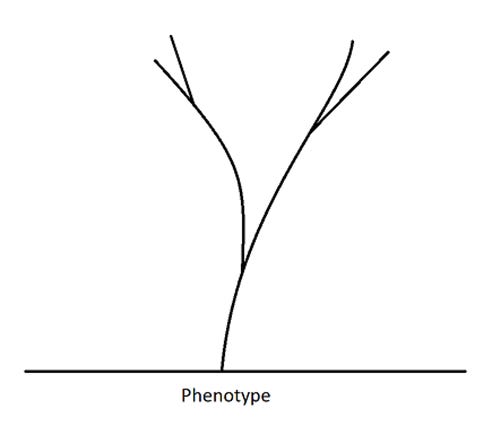

(1) Demographic extinction: the population of Homo sapiens dwindles to zero, thus disappearing entirely. This could happen suddenly or gradually, as the image below illustrates. Theoretically, demographic extinction could occur almost instantaneously, if a high-powered particle accelerator were to “nucleate” a vacuum bubble. This bubble would expand in all directions at close to the speed of light, destroying everything in its path. Most extinction-causing catastrophes, though, would unfold over years or decades, as in the case of thermonuclear war and global pandemics. There could also be infertility scenarios that cause the human population to drop over centuries, until no one is left.

(2) Phyletic extinction: this would occur if our species disappears entirely because it evolves into one or more “posthuman” species. One way this could happen is through cyborgization, whereby we integrate technology into our bodies, reengineering ourselves in the process. The result could be a new species of posthuman cyborgs. Or we might replace our biological substrate entirely with something artificial, as would happen if we “uploaded” our minds to computers. If either scenario were to obtain and Homo sapiens were to disappear, we would have undergone phyletic extinction. However, even if we choose not to reengineer ourselves, natural evolutionary mechanisms like natural selection, genetic drift, random mutation, and recombination will eventually shape us into a new species, though this will take tens or hundreds of thousands of years.

(3) Terminal extinction: this would happen if Homo sapiens were to disappear entirely and forever, which could occur as a result of either demographic or phyletic extinction. The crucial idea behind terminal extinction is that it adds a condition of permanence: never again are there any instances of our kind in the universe. Why is this distinction important? There are many reasons. I’ll give two: first, it’s necessary to make sense of past thinking about human extinction. Recall from earlier that Xenophanes posited a theory in which humanity disappears for one stage of the cosmic cycle, but this is only ever a temporary state of affairs. Hence, according to Xenophanes, we will someday become demographically extinct, but we will never become terminally extinct. In fact, we have undergone demographic extinction an infinite number of times in the past, and will undergo this an infinite number of times in the future. Humanity always reappears, though.

Another example is futurological rather than historical: some scholars have argued that technologically advanced civilizations choose to “aestivate,” which refers to a state of dormancy during a warm period. (Hence, some animals aestivate in the summer, while others hibernate in the winter.) Because the universe will be cooler in the future, in accordance with the Second Law, computational costs will be lower. If a civilization values computation, it may decide to become dormant. One way of becoming dormant would be to intentionally cause its own demographic extinction, so long as there was some way of reviving the civilization later on, thereby avoiding terminal extinction. The distinction between demographic and terminal extinction could thus become very important to our own civilization in the future, depending on what it values.8 Which brings us to:

(4) Final extinction: this would happen if Homo sapiens were to disappear entirely and forever without leaving behind any successors. What motivates this category is the idea that what happens after we disappear could make a huge difference to how one assesses our disappearance. If Homo sapiens disappears but we leave behind a population of intelligent machines that carry on our civilization, scientific projects, and “values,” some would not see this as bad. Many futurists have argued that we should want this to happen. On their view, terminal extinction might very well be desirable, so long as we avoid final extinction. Others would say that terminal extinction might be bad, but it would be much less bad if it didn’t coincide with final extinction, meaning that having successors would mitigate the badness of our species no longer existing.

Notice that, while final extinction assumes terminal extinction, it is incompatible with phyletic extinction, since becoming phyletically extinct would entail that we have had successors. Also note that I used the phrase “genealogically or causally related to us” earlier to make room for the scenario above, in which we create successors that aren’t clearly part of our evolutionary lineage itself, such as intelligent machines. If we were to evolve through cyborgization or natural selection into a new posthuman species, then we would be genealogically related to these future beings. But if we were to create an entirely new lineage, we wouldn’t be related to them in this way, although the entities in this new lineage would be causally connected to us, by virtue of us having created them. By using the phrase “genealogically or causally,” I’m leaving open the possibility that our descendants belong to a distinct lineage, one that we bring into existence.

(5) Normative extinction: this would happen if we have successors, but these beings were to lack something—a capacity, attribute, or property—that is normatively necessary for them to count as “human.” This is where the normative definitions of “human” and “humanity” become very important. Imagine a scenario in which we evolve into a new posthuman species, or replace Homo sapiens with a population of intelligent machines, but over time these descendants of ours lose the capacity for conscious experience. Perhaps they continue to develop science, create works of art, and debate philosophy, yet there is nothing it is like to be them. They are philosophical zombies with no inner qualitative mental life. Since consciousness is necessary for sentience, these future beings wouldn’t count as human, if “human” is defined as “sentient beings that matter.” Consequently, humanity would no longer exist, which is enough to satisfy the minimal definition of extinction.

The same goes for definitions of “humanity” that emphasize moral status, since many philosophers believe that having moral status requires, at minimum, the capacity for conscious experience.9 Or imagine a scenario in which our descendants become much less “intelligent” than us. On the most capacious definition above, where “humanity” denotes “Earth-originating intelligent life,” these future beings wouldn’t be human, even if they were conscious. If one believes that the continued existence of “humanity” is important, this outcome might constitute a tragedy on par with final human extinction.

The key idea behind normative extinction is that it matters not just that we have successors, but what these successors are like.

(6) Premature extinction: this introduces the idea that the timing of our extinction, in any of the senses above, matters. If one holds a teleological vision of the human enterprise as striving toward some treasured goal, then one might claim that disappearing before we reach this goal would be worse than disappearing after it. Perhaps the goal is to create a techno-utopian world among the stars, or to construct a complete scientific theory of everything. One might argue that extinction after achieving these goals would still be very bad, but extinction before would be a much greater tragedy. On this account, what matters isn’t just whether our extinction happens, but when.

Distinguishing between these extinction scenarios is important because some positions within Existential Ethics see certain types of extinction as very bad, while assessing others as neutral or even good under certain circumstances.10 Other positions evaluate all the scenarios the exact same way, while still others point to just a single type of extinction as important. Failing to recognize that “human extinction” is highly polysemous—that it can have many different meanings—is a recipe for confusion and merely verbal debates, in which people appear to have a substantive disagreement, when in fact they’re using the same words to denote quite different things. For existential ethicists to make progress in the field, it is crucial for them to understand these different scenarios and the complex ways that different definitions of “human” fit with each.

So, whenever someone asks you: “Would human extinction be bad?,” the first thing you should do is huff back: “What do you mean by ‘human’?” and “What do you mean by ‘extinction’?” Only once you’re clear about the question can you begin to answer it coherently.

2.4 The Prototypical Conception

If “human extinction” can mean so many different things, what do most people have in mind when they think of this happening? What is the “prototypical conception” of human extinction? My hypothesis in the book is that this conception consists of three components.

First, most people naturally assume that “human” means “Homo sapiens,” rather than “future conscious beings with a certain moral status that are genealogically or causally related to us.” Second, in my experience, if someone is asked to define “extinction,” they will typically give the definition of “demographic extinction.” This is, in fact, the standard dictionary definition. If I follow-up with a question about whether our extinction might be temporary, they respond that it would surely be permanent (terminal extinction), and if pressed further, they tend to converge on the notion of final extinction: our extinction would be a complete and final end to the entire human story, an exclamation point at the end of this whole journey we are on, with nothing after it. Hence, most people take “human extinction” to mean “the final extinction of Homo sapiens.” But there is also an etiological, or causal, component of this conception, as most people automatically picture the final extinction of Homo sapiens happening as the result of some catastrophe. In other words, few if any of us imagine everyone on Earth choosing not to have children when we think of human extinction. Rather, we visualize a nuclear war, global pandemic, or asteroid impact when the idea comes to mind.

This is the prototypical conception, the primary focus of History #1. To be clear, there were people who addressed other types of extinction—Xenophanes was concerned with demographic extinction, and some writers after Darwin considered phyletic extinction—but in general, most thoughts about the possibility, probability, and so on, of human extinction involved the prototypical conception. Whether I am right about this being the most common conception today is not clear. Perhaps psychologists or sociologists will conduct a survey to test the hypothesis.

2.5 Going Extinct Versus Being Extinct

There is one last set of distinctions that are just as important as the six extinction scenarios. Consider the question: Are you afraid of death? Some people will say that the only reason they fear death is the suffering that dying might involve. Others will say that they’re afraid of not just the suffering but the subsequent state of no longer existing. For them, non-existence is a source of death’s terror in addition to the harms of dying. Moving from the level of individuals to the level of our species—from death to extinction—one can make an identical distinction between the process or event of Going Extinct and the state or condition of Being Extinct. This is an absolutely crucial distinction for Existential Ethics, which is orthogonal to every type of extinction outlined above. That is to say, there is Going Extinct and Being Extinct in the demographic sense; Going Extinct and Being Extinct in the phyletic sense; and so on. Whether one sees Being Extinct as ethically and evaluatively important, or whether one believes that the details of Going Extinct are all that matter, makes all the difference when it comes to which position one accepts within Existential Ethics.

What sorts of “details” about Going Extinct might be important? There are several. The most obvious is whether human extinction, however defined, is the result of natural or anthropogenic causes. There is nothing immoral about an asteroid hitting Earth and killing every human, since asteroids are not moral agents: they cannot be held morally responsible for anything. Ethics only cares about the actions of moral agents—creatures capable of being held morally responsible for their choices—and hence asteroid impacts fall outside the purview of ethics. However, if astronomers were to see this asteroid heading toward Earth, but instead of sending a spacecraft to redirect it they keep their discovery a secret, then this might well be an ethical issue, as we might count it as “anthropogenic” rather than “natural,” even though the asteroid itself is a natural phenomenon. Hence, where one draws the line between natural and anthropogenic is very important. I explore this in chapter 7 of the book, but won’t say anything else about it here.

Another distinction is whether Going Extinct is voluntary or not. Some philosophers argue that if causing or allowing our extinction were entirely voluntary, without any coercion at all, then it would not be wrong. Others claim that it would be wrong—perhaps very wrong—even if everyone on Earth voluntarily gave it a big thumbs up. For them, the voluntariness of extinction is morally irrelevant. A final distinction concerns how quickly Going Extinct happens. According to some philosophers, if our extinction were to happen in a flash without any prior warning, it wouldn’t be bad, because no one would suffer. (I mentioned above that this could theoretically happen. One could even imagine an omnicidal billionaire in the future building a particle accelerator in hopes of “nucleating” a vacuum bubble to destroy all life in an instant.) However, some of these very same philosophers argue that if Going Extinct were to cause suffering, then it would indeed be very bad.

In sum, it’s absolutely vital to distinguish between Going Extinct and Being Extinct. And there are many ways that Going Extinct could unfold that are ethically and evaluatively relevant, such as whether it is anthropogenic or natural, voluntary or involuntary, and instantaneous or drawn-out.

2.6 Positions Within Existential Ethics

We have now established a theoretical framework for making sense of Existential Ethics. Before turning to the historical development of this field, though, it may be worth engaging in one last abstract philosophical task: sketching the different positions that one could take on the subject, based on the distinctions made above.

There are three main classes of views within Existential Ethics. I call these equivalence views, further-loss views, and pro-extinctionist views. There are two additional positions that are also important: the default view and the no-ordinary-catastrophe thesis. Let’s examine these in turn, skipping over the no-ordinary-catastrophe thesis for now. To keep the conversation manageable, I will assume that we are talking about final extinction unless otherwise noted.

(1) The default view simply states that human extinction would be bad if the process or event of Going Extinct were to cause suffering and/or cut lives short. I call this the “default view” because virtually everyone accepts it, even most philosophers who are for extinction. The only people who might reject it are sadists and ghouls who derive pleasure from the thought of 8 billion people—including themselves—dying. The default view is mostly uncontroversial.

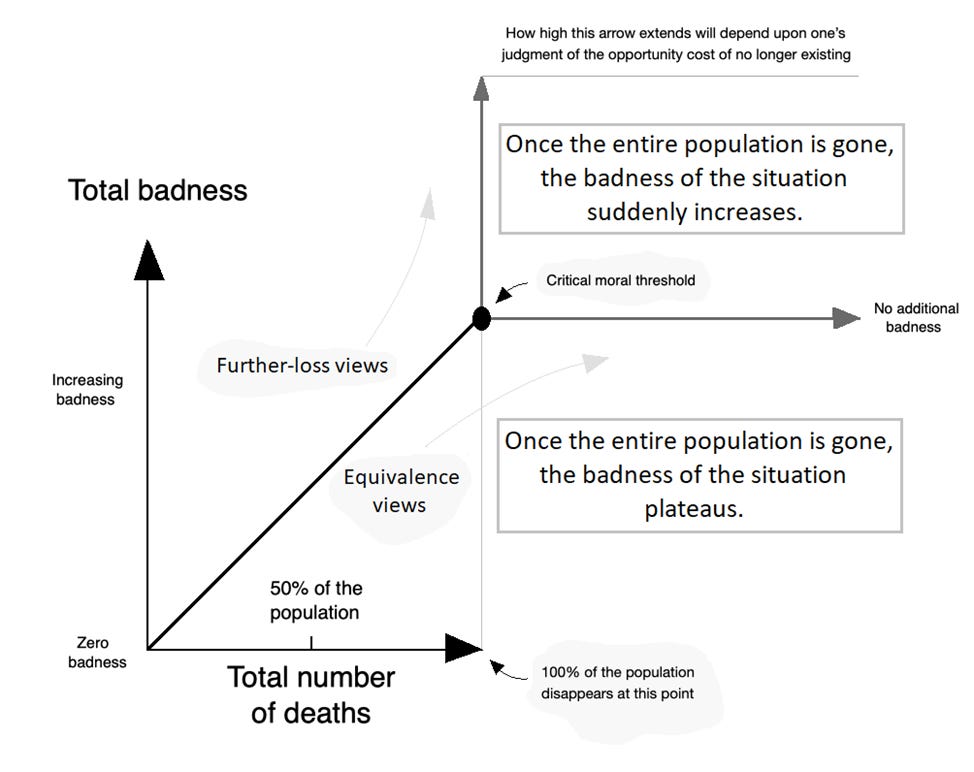

(2) Equivalence views claim that the default view is the entire story. Those who accept the equivalence view would argue that the badness or wrongness of our extinction is entirely reducible to the badness or wrongness of Going Extinct. If there is nothing bad or wrong about Going Extinct, then there is nothing bad or wrong about extinction, period.11 Put yet another way, the badness/wrongness of human extinction is equivalent to the badness/wrongness of how Going Extinct unfolds, which is why I call these “equivalence views.”

To illustrate, imagine two worlds: in World A, there are 11 billion people, while in World B, there are 10 billion. An identical catastrophe happens in each, causing exactly 10 billion people to perish. At a high level of abstraction, we can say that one event happens in World A—the death of 10 billion people, leaving 1 billion survivors—while two events happen in World B—the death of 10 billion people and the extinction of humanity. The important question is: does this second event in World B make any ethical or evaluative difference? Is the catastrophe in World B worse than the catastrophe in World A because it eliminates humanity? If a homicidal maniac named Joe kills 10 billion people in each world, does he do something extra wrong in World B compared to World A?

An equivalence theorist will say that the catastrophe in World B is no worse than the one in World A, and that Joe does not do anything extra wrong in World B compared to World A. Why would someone hold this view? One popular answer is that if there’s no one around to bemoan the non-existence of humanity, then Being Extinct cannot be bad or wrong to cause—it harms no one.12 The process or event of Going Extinct may very well be bad or wrong, and hence the equivalence theorist would say that, by killing 10 billion people, Joe did something unimaginably awful. But once the deed is done and humanity is no more, who exactly is harmed by Being Extinct? No one, which is why all that matters for equivalence theorists are the details of Going Extinct.

An interesting implication of this view is that there is no unique moral problem posed by our extinction. Everything one might say about the badness or wrongness of extinction can be said in ordinary moral language: 10 billion people suffering and dying in World B is very bad because human suffering is bad. Killing 10 billion people in World B is very wrong because murder is very wrong. The fact that humanity itself disappears in World B is just not morally relevant. Many philosophers throughout history have held equivalence views, and I myself am most sympathetic with it.

(3) Further-loss views strongly disagree with these claims. Advocates of such views would argue that, when assessing the badness/wrongness of human extinction, one needs to examine two things: first, the details of Going Extinct. Did the process of dying out cause suffering or cut lives short? And second, certain additional losses or “opportunity costs” associated with Being Extinct. What might these additional losses be? Some would point to all the happiness that could have otherwise existed, if humanity had survived. On one count, there could be at least 10^58—that’s a 1 followed by 58 zeros—people in the future. If these people were happy on average, then the total amount of happiness lost by not existing would be astronomically large. Others would point to goods like the further development of the sciences, the arts, and even morality itself. Being Extinct would erase future accomplishments in these domains before we have a chance to draw them.

Further-loss theorists thus argue that the badness or wrongness of extinction goes above and beyond whatever harms Going Extinct might entail: there are also various further losses, associated with Being Extinct, that are ethically and evaluatively important. An interesting implication of this is that our extinction could still be very bad or wrong even if there is nothing bad or wrong about Going Extinct. Imagine that everyone around the world voluntarily chooses not to have children. Over the course of 100 years or so, the human population dwindles to zero. Would this be bad or wrong? Equivalence theorists would say “no,” since there is nothing bad or wrong about not having kids. Further-loss theorists would say “yes,” because dying out would foreclose the realization of all future goods and happiness.

Returning to the Two Worlds thought experiment above, further-loss theorists would say that the catastrophe of World B is much worse than the catastrophe of World A, and that Joe does something extra wrong in World B compared to World A. How much worse or more unethical is the catastrophe of World B? It depends on one’s assessment of the further losses: the greater the losses arising from Being Extinct, the more tragic World B will appear.13

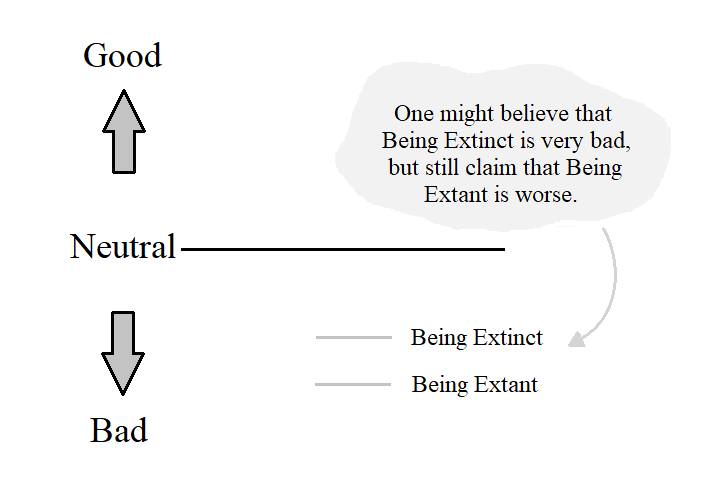

(4) The last position within Existential Ethics is what I call pro-extinctionism. This states that Being Extinct would in some way be better than Being Extant, or continuing to exist. As alluded to earlier, nearly all pro-extinctionists accept the default view: they believe that if Going Extinct involves harms, it would be bad or wrong. They simply add that the subsequent state of no longer existing would be better. Notice that “better” does not imply “good.” One could hold that Being Extinct is bad—even very, very bad—and still believe that Being Extant is worse.

The main problem for pro-extinctionism concerns how to get from here to there, from Being Extant to Being Extinct. There are three main items on the menu of options: antinatalism, whereby enough people around the world stop having children; pro-mortalism, whereby enough people around the world take their own lives; and omnicide, whereby someone or some group kills everyone on Earth. The large majority of pro-extinctionists have held that antinatalism is the only morally acceptable means of transitioning to the state of Being Extinct, although a very small number have advocated for pro-mortalism and even omnicide.

Returning once again to the Two Worlds thought experiment, pro-extinctionists would claim that if they were forced to choose between World A and World B, they would pick World B. Why? One answer is that by causing our extinction, this would prevent a potentially large amount of future human suffering from existing. Others would point to environmentalist reasons, arguing that humanity has been a hugely destructive force in the biosphere, and hence without us, the natural world would be better off.

2.7 Which Type of Extinction Matters?

We can see from this brief survey just how important the distinction between Going Extinct and Being Extinct is for Existential Ethics. But what about the different types of human extinction? How do they fit into this picture? Let me illustrate with a few examples.

First, let’s say that you hold a further-loss view according to which what matters is that the future contains maximum value. You also believe this value cannot be created if our descendants lack a certain moral status, are incapable of conscious experiences, and so on—properties that some of the normative definitions of “humanity” attempt to capture. Does it matter whether Homo sapiens persists? No. So long as we have successors with the right properties, the future could still contain large amounts of value. In other words, the terminal extinction of Homo sapiens would not be inherently bad or wrong to bring about. The only types of extinction that must be avoided, on this view, are final and normative extinction.14

We may still have practical reasons to avoid demographic extinction in the near future, since if this were to happen tomorrow, it would almost certainly coincide with final extinction, by way of terminal extinction.15 But if we are, as some claim, on the cusp of creating sentient, intelligent machines that could replace us, then demographic extinction would only be important to avoid if it were to happen before these machinic replacements arrive. Our disappearance after they arrive wouldn’t be any great tragedy, since these posthuman beings could create maximum value in the universe even if we no longer exist—indeed, they may be much better positioned to do this than we are.16 This is why some further-loss views will identify final and normative extinction as the only two scenarios that must be prevented at all costs.

What about equivalence theorists? Since they do not see extinction as posing any unique moral problem, their view applies to every type of human extinction equally. Would demographic, phyletic, terminal, and so on, extinction be bad or wrong? It depends on how these come about. If there is nothing bad or wrong with Going Extinct in any of these senses, then there is nothing bad or wrong, period.

As for pro-extinctionists, if the aim is to prevent future human suffering or the harms that we cause to the biosphere, then one should hope not just that our species dies out but that we don’t have any successors. If Homo sapiens disappears while leaving behind successors who are capable of suffering or destroying the biosphere even more, the problem that pro-extinctionism aims to solve will remain. Hence, when most pro-extinctionists talk about “human extinction,” they are referring to “final human extinction.” This is the one type of extinction that would guarantee no more human suffering or environmental destruction in the future. There are some interesting nuances here, but I will pass over them for now.

We can now see why disambiguating the term “human extinction” is so important. The fact that so many disparate scenarios are referred to by the same term can easily lead to confusion and merely verbal debates. The types of extinction that the three main positions within Existential Ethics target may be very different. Understanding this is necessary for the field to progress.

Section 3. History #2—Existential Ethics

3.1 The Four Waves

Having established a theoretical framework for making sense of Existential Ethics, we can now turn to its historical development. In Part II of the book, I suggest that History #2 can be partitioned into four vaguely defined “waves,” which align with the five-part periodization of History #1 in a somewhat complicated way. Whereas the existential moods of History #1 are a real feature of the Western historical record, I take these waves to be nothing more than a useful way of organizing History #2. Let’s consider them in turn:

3.2 The First Wave

The first wave began with the birth of Existential Ethics in the 19th century. This makes sense, since there’s no especially good reason to reflect on the ethics of something that no one believes is possible or could actually happen. In particular, it was the second half of the 19th century that witnessed more than a few philosophers addressing the core questions of Existential Ethics. However, there were earlier writers who touched upon the topic, all of whom held either non-traditional religious views or rejected religion altogether.

One was the Enlightenment deist Montesquieu. In his 1727 epistolary novel Persian Letters, he argues that the human population is declining, and that if this continues, humanity will cease to exist. Of note is that he—speaking through a character in the novel—describes this event as “the most terrible calamity that can ever happen in the world.” What I find interesting about this is that Montesquieu seems to point at Being Extinct as a source of badness, rather than the harms that Going Extinct might cause, although he did not elaborate on why. Perhaps he believed the answer was obvious: a world without us would be missing something important. As the philosopher Immanuel Kant expressed this very idea in 1790, “without men the whole creation would be a mere waste, in vain, and without final purpose.”

The first writer to elaborate a further-loss view in print was probably Mary Shelley. In her 1826 novel The Last Man, she made two interesting claims: first, she foregrounded the possibility that Going Extinct could introduce extra suffering to the last generation on Earth, because it’s the last generation. A common response to someone going through a difficult time is to say that “it’s not the end of the world.” But if it is the end of the world, this source of comfort won’t work. The final generations, and the last remaining people of those generations, may experience feelings of dread, hopelessness, and loneliness that other catastrophes might not induce. This is the central thrust of the “no-ordinary-catastrophe thesis,” mentioned in the previous section. Although one might find this thesis a bit peculiar at first, many existential ethicists have referenced it.17 Shelley was among the first.

But Shelley also suggested that our extinction—which she seemed to understand in a naturalistic sense—would be bad independent of all the suffering caused by Going Extinct. At one point in the novel, she lists “adornments” of humanity like knowledge, science, technology, poetry, philosophy, sculpture, painting, music, theater, and laughter as further losses that would make our disappearance extra tragic. Without humanity, none of these would exist, which points to Being Extinct as a source of badness, too.